Posted February 20, 2024

By Greg O’Brien

“Do not go gentle into that good night”

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

“Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

“Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Dylan Thomas

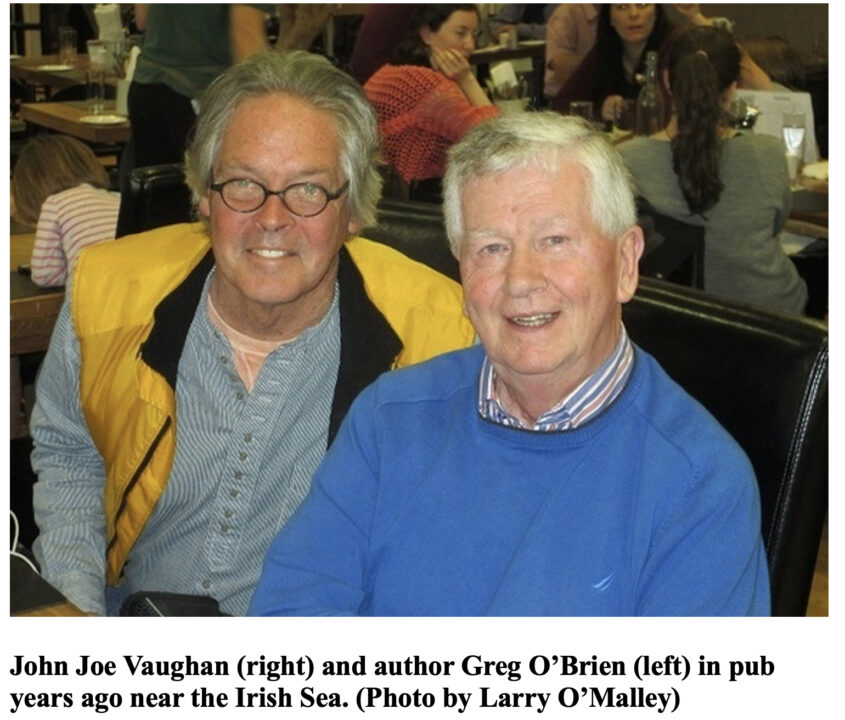

My close Irish friend John Joe Vaughan is raging today on the last lap of his marathon against Alzheimer’s. He will not go gentle into that good night, at least not without a bit more of a fight, an example for all worldwide on this journey.

The 88-year-old from New Ross in County Wexford south of Dublin, the ancestral home of the Kennedy family has an incredible personal history himself. He’s a father of eight, a devoted husband, a grandfather of 17, a retired teacher and school principal who was raised in rural Marshalstown without electricity and paved roads. He has lived a life of commitment, devotion, and strong faith. He’s always been a fighter.

“My Dad is still fighting on his way out; you would be so proud of him; that’s how I want to remember my father, not the shell of the man he is today,” John Joe’s daughter Rena Geary wrote me in a text from the family home near the Irish Sea. Rena just returned from her visit to Wexford—a last goodbye to her father, she fears. Her father recently had a fall and a stroke that left him unable to walk and with limited speech. Given the struggles of his fight with Alzheimer’s, this added burden has almost broken the man.

Says Rena, “Dad is fighting as hard as he can to hang on to whatever dignity he has left. He no longer can speak clearly, and struggles to pull the words when he is trying to get his point across. I had to lean in closely to try to understand what he wanted or needed, and when I missed what he was trying to tell me, I could see the frustration in his eyes. All I could do was hold his hand and tell him everything would be ok.”

Rena says her father still carries the burden of making sure everyone is cared for: Does his wife, Peggy, called “Mam,” have enough money, and who’s paying for where he is now living—a nursing home back in Enniscorthy where he first started his teaching career?

“I said my final goodbye to Dad, no easy task, and hope for him that his fight ends sooner rather than later. The man deserves some peace. He deserves not to be fighting the demons of Alzheimer’s any longer. My mother says she prays that the good Lord will take him out of his pain and the frustration of this horrible disease.”

Dylan Tomas, one of John Joe’s favorite poets, would also be proud of him.

I met John Joe about ten years ago at Logan Airport in Boston, having just returned from another trip to Ireland with family. There are 48 branches of our collective family tree, and 47 of them can be traced back to Eire. John Joe had just arrived from Dublin to visit his daughter, Rena, now living in New Hampshire with her husband Ed. While I was on my cellphone responding to a queue of backlogged voicemails, Rena began waving at me. She recognized me from a photo in my book, On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s.

“I want you to meet my father,” Rena told me, noting that her dad had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and was reticent to talk about it until reading On Pluto. She had given him a copy.

“This guy gets me,” Rena said her father told her. “I thought I was alone, but I’m not; he gets me!

I was humbled, but that was just the beginning.

I also deal with the demon Alzheimer’s, which took my maternal grandfather, my mother, and my paternal uncle, and before my father’s death, he too was diagnosed with dementia. The Lord works in mysterious ways. What are the chances of meeting up with Rena’s father?

John Joe had a smile that would light the River Liffey and the handshake then of a heavyweight champion. He embraced me, eyeball to eyeball, and I saw the tears streaming down the side of his creased, righteous face. Though we lived thousands of miles apart, yet we were connected for life by a disease that will take our lives and the lives of millions.

And so, it is with those worldwide with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

Notes the Alzheimer’s Disease International, “Someone in the world develops dementia every 3 seconds. There are over 55 million people worldwide living with dementia.” Without a cure, “this number will almost double every 20 years, reaching 78 million in 2030 and 139 million in 2050. Much of the increase will be in developing countries. Already 60% of people with dementia live in low- and middle-income countries, but by 2050 this will rise to 71%. The fastest growth in the elderly population is taking place in China, India, and their south Asian and western Pacific neighbors.”

And so, I cried, too.

“I know how it feels,” John Joe said to me. “We fight together now as brothers, right? We fight together?”

“Right!” I said.

And we have.

Yet now I’m feeling a bit alone in the throes of losing my friend.

Logan Airport was no brief encounter. John Joe invited me, along with my wife Mary Catherine and some family members, to spend a week that summer writing and just hanging with him over a few pints at his family’s summer cottage on the Irish Sea in the fishing village of Duncannon, out on a peninsula at the mouth of rivers Barrow, Nore, and Suir. The rivers overlook the majestic 800-year-old Hook Head Lighthouse. It’s one of the oldest working lighthouses in the world where legend has it that monks from the nearby Dubhan monastery lit fires in the fifth century to warn ships of the treacherous rocks. Today, the Fresnel lens flashes every three seconds; I counted the blinks in my bedroom each night as I tried to sleep, captivated by the night sky flecked with infinite specks of white, reflecting on the lighthouse and the craggy peninsula just across from the narrow strait called Crooke. It’s a place where, in the mid-1600s, British military tactician Oliver Cromwell, charged with defeating Ireland’s rebellious Confederate Coalition, declared that he would take the country “by Hook or by Crooke,” a declaration that would last in the vernacular for hundreds of years.

And so, John Joe and I met by Hook or by Crooke in County Wexford where my mother’s family hailed. John Joe’s mother also died of Alzheimer’s and his older brother was stricken with the disease, as well.

“I’m emotional about this,” John Joe tells me. “I can’t control that; it’s the card I was dealt. What can you do about it? I refuse to give in. So, I fight on. I retreat into myself and fight on. It makes me nervous—the progression I have to face.”

Once quick-witted, gifted with the Irish natter, and an accomplished oil painter, John Joe is now slower to the draw, yet in the past, he tried to use humor to make fun of the fact that he can’t remember. A notable man, an incredible teacher to his children, his students, and to me, John Joe always had a fascination with the world beyond. He often encouraged those around him to open their minds to broader horizons. Now his world is shrinking in disturbing ways—the muscle memory is gone; the indelible images of the past, analogous to a palate of oil colors ready to paint a canvas, are lost.

John Joe has always been a warrior—an artistic soft side and a thriving right brain until recently that guided him back to his love of art, a self-healing therapy for the ravages of a disease that robs a sense of self. He used to spend hours painting in oils; it was a passion, yet a challenge, remembering what colors to use. He devised a scheme of selecting the proper oil colors and labeling the colors to choose the right ones.

Art—whether painting, music, or writing— stimulates the brain, stirs memories and reduces agitation caused by Alzheimer’s. By his own admission that day, John Joe is no Michelangelo, yet his work is inspiring in so many ways. Upon my visit to Duncannon, he presented me with an impressive painting of Hook Head Light. It hangs now in my studio.

“What scares me about this disease,” he says then over another sip of his pint, “is the loss of memory and the inability to carry a conversation. The brain just isn’t processing; it’s stalled. It’s embarrassing. So, I often avoid conversation. I retreat into myself, and at times deal with rage. People who know me say, ‘He’s changed a lot.’’

What hasn’t changed about John Joe is his heart. Alzheimer’s drives one from the mind to the place of the heart, the soul. “I may have tears in my eyes,” he says before we leave the pub, “but I’m not crying out of sorrow. It’s part of what I’ve been handed. I was blessed with a good family that gives me strength. I have no cause for complaint. I laugh, like you, at how long it takes me to remember.”

John Joe had a laugh then, the kind of gurgle one would expect from a leprechaun. I’m looking for the rainbow now, the pot of gold. “If a cure comes,” he says. “It will likely come from America. I hope you call me up someday and say: ‘John Joe, I have a little pill for you…’”

“You’ll get the first call,” I promised him.

Here we were: two Irish guys coming full circle near the Irish Sea, separated by 2,992 miles, connected for a lifetime by a disease that will steal our minds, but not our souls.

In some ways, it doesn’t get any better. Safe Travels, John Joe. “Do not go gentle into that good night”…Love you!

(Greg O’Brien, a career journalist, is the author of On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s, and the subject of a Los Angeles-produced documentary about his journey that has aired nationally on PBS stations—“Have You Heard About Greg”)