Posted February 3, 2024

By Greg O’Brien

“We all long for Eden, and we are constantly glimpsing it: our whole nature at its best and least corrupted, its gentlest and most human, is still soaked with the sense of exile.”

J.R.R. TOLKIEN, THE LETTERS OF J.R.R. TOLKIEN

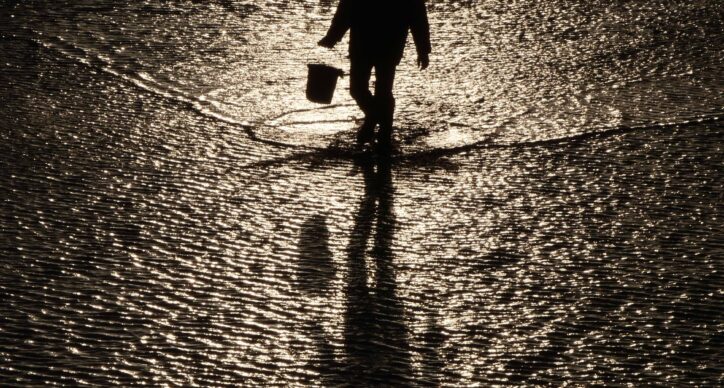

I am soaked today in exile, as are others in this disease, as Alzheimer’s ensues—one foot on the terra firma we call reality, the other south of Eden—a realm beyond the physical.

But what is reality? I always thought I knew.

When the brain—our perceived essence—begins to shut down, the spirit, our true essence, I believe, pursues. The physical now seems at times a veneer to me, a facade, a made-for-TV movie. Yet, at 73, I’m still conflicted about leaving family and friends behind. So I straddle in my search for Eden.

It’s the journey from the cradle to the grave. We’re all on it, at various way stations. We all find our own way in life; mine is just one of many. The key is to keep seeking.

Decades ago, as a young, brash journalist, I thought I had all the answers, and that my job was to impart such wisdom in my terms, my narrative. I know now in Alzheimer’s that I clearly don’t have the answers—greater motivation to sift the real from the imagined, a vetting for me confounded by fighting off the misperceptions and the progressions of this disease. Less and less, I do not fully trust my brain anymore, so I follow my heart, and that, for me, has opened windows of hope, greater intuitiveness.

I know I will leave this planet one day without all the answers from a disease that the experts say can take 20-to-25 years to run its serpentine course—like having a sliver of your brain shaved every day. But I’m committed to running the race of faith and, in the process, seeking redemption. I’m no Puritan, no altar boy today, just a stubborn Irish guy striving beyond my grasp for what is real. Alzheimer’s has brought me to this place—the pursuit of truth, wherever that takes me.

I am thankful for that, and for not feeling sorry for myself along the way.

Early on, I was inspired by the courage of award-winning Philadelphia Inquirer sportswriter Bill Lyons, who died from Alzheimer’s a few years ago after a long battle. He wrote powerfully of his disease: “Never, Ever Quit,” he urged.

Lyons personalized Alzheimer’s, calling his intruder, “Al.” I’ve taken to the name myself. At first glance, “Al” is somewhat of a submissive, disarming, forgetful sort, who, over time, takes on the persona of a Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs in a grisly swath of mass murders. “Al” unwittingly may be here to teach our generation something, as collectively we wrestle with losing car keys, forgetting where the car is parked, walking into rooms with no clue of why we are there, and other, far more wrenching disconnects to come. Some call it age, “Al” calls it taking no prisoners. But as Baby Boomers in their 50s, 60s, and 70s begin their final laps in life, there is a sense of urgency among many to do more good on the way out, create new memories. Good often comes from striving through imperfection.

“Al is an insidious and relentless little bastard,” wrote Lyons, “a gutless coward who won’t come out and fight. Instead, he lies in ambush in my brain, and the only way I can put a face on him is to look in the mirror…I should very much like to kick Al’s ass.”

Lyons in his fluent columns conceded that he was not alone in this struggle; neither are others with this disease—thanks to faith, selfless family, friends, caregivers, doctors, researchers, and a spate of national, regional, and local support groups. But when the light in the brain flickers, many often withdraw to the bunker, lashing out in gut anger, retreating to our inner selves, keeping our heads down below the tracer bullets.

My anger at “Al” is rising within, yet often misplaced, spraying uncontrollable ire in all directions, usually at loved ones. I’ve come now to understand that Alzheimer’s must be fought on both medical and spiritual grounds; I am humbled by such grace. My pastor, Doug Scalise, has grounded me in that.

Pastors must deal with all sorts of cycles and spins. At Brewster Baptist Church on bucolic Main Street on Outer Cape Cod, Scalise oversees what he calls a “big tent” church that serves the full range of political, cultural, and social perspectives—all joined together in the cohesion of faith. No one is judged here; we just worship. An ecumenical sort myself, I attend services here as well at times at the Catholic church down the road. I’ve also attended services at a synagogue, and spoke once at the Unitarian Universalist Church. So I guess I’ve hit for the cycle.

Like all of us, Scalise knows his time on earth is fleeting. Not long ago, he had a brush with death, an often fatal heart condition called the “Widow Maker”—a 98 percent blockage of the anterior interventricular branch of the left coronary artery. Emergency surgery at Cape Cod Hospital saved his life. “We all have a shelf life,” he tells me, as I reach out for guidance. “We’re designed with built-in obsolescence.”

“Last time I checked,” he adds, “mortality was hovering at about 100 percent.”

Scalise indeed knows first-hand what it’s like to walk through the Valley of Death. In fact, he has a copy of the 23rd Psalm in his office: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil…”

The verse speaks to me.

“You can’t helicopter over the valley,” says Scalise. “You gotta walk through it. Mountain hikers know this. The valley is dark and often you can’t see around the next corner; you just have to keep walking.”

“Alone?” I ask.

Scalise points to a photo of a flock of high-flying geese. With the juxtaposition of the photo, it appears the geese are flying past the moon. While we’re all told in life to soar like eagles, he says, geese fly even higher in the flock, a “V” formation.

“It’s a study of teamwork,” he adds. “Geese in formation take turns in the lead, breaking the wind; others in the flock draft off the lead, with each bird honking encouragement and benefiting from the bird in front. They all take turns at the front, the hardest role. It’s an exercise in leadership, an exercise of the heart. No one is left alone. And so it should be in life.”

“Never stop speaking from the heart,” he urges. “When the body weakens with disease, the heart—the soul—grows stronger. It survives for eternity.”

“Then why am I so angry?” I ask Scalise.

“You have a right to be angry,” he tells me. “It’s okay to be angry at God. The book of Psalms is filled with such raw emotion, asking the Lord to ‘rouse thyself.’ We all think God is sleeping at times. Wake up, we say, get on the job! The anger is understandable, yet misdirected in places. God, I believe, doesn’t impart disease, but the Lord will use illness to bless. In illness, we have to look for the blessing, the lesson of giving thanks and gratitude for what remains… God has work for you; it’s not your time.”

Weeks later in a sermon, Scalise reinforces the point. He tells the congregation it has a choice when walking through the “Darkest Valley” times of tribulations that can make or break us. “Don’t squander the opportunity,” he counsels, urging his flock to walk in endurance, hope, and love. “Grow through what you go through,” he says, offering a parable of a carrot, egg, and coffee beans in boiling water.

“A young woman,” he says, “went to her mother and told her about her life and how things were so hard for her. She didn’t know how she was going to make it and wanted to give up. She was tired of fighting and struggling. It seemed as one problem was solved a new one arose. Her mother took her to the kitchen. She filled three pots with water. In the first, she placed a carrot, in the second she placed an egg, and in the last she placed ground coffee beans.

“The woman let them sit and boil without saying a word. After a while, she turned off the burners. She fished the carrot out and placed it on a dish. She pulled the egg out and placed it in a bowl. Then she ladled some coffee into a mug.

She asked her daughter, “What do you see?”

“A carrot, an egg, and coffee,” the daughter replied. Her mother brought her closer and asked her to feel the carrot. The daughter did and noted that it was soft. The mother then asked her to take the egg and break it. After pulling off the shell, she observed the hard-boiled egg. Finally, the mother asked her to sip the coffee. The daughter smiled, as she tasted its rich aroma.

“Then the daughter asked, ‘What’s the point?’

“Her mother explained that each of the objects had faced the same adversity, boiling water, but each reacted differently. The carrot went in strong, hard, and unrelenting. However, after being subjected to boiling water, it softened and became weak. The egg had been fragile. Its thin outer shell had protected its liquid interior. But, after being through boiling water, its inside became hardened. The ground coffee beans were unique, however. After they were in the boiling water they had changed the water.

“’Which are you?’ the mother asked her daughter. “When adversity knocks on your door, how do you respond? Are you a carrot, an egg, or a coffee bean?’”

Pastor Scalise looks up. “Which one are you?” he asks the congregation.

I’m ducking in the pew now, thinking he’s speaking straight at me. Scalise is dialed into me.

Scalise then goes on to tell another parable about a farmer talking to a passerby about his soybean and corn crops. Rain at the time was abundant, and the fields were fertile, Scalise notes, adding that the farmer’s comments to the man were surprising.

“My crops are especially vulnerable,” he told the man. “Even a short drought could be devastating.”

“Why?” the man asked.

“While frequent rain is a benefit,” the farmer said, “during such times of rain plants are not required to push roots deeper in search of water. The roots remain near the surface. And a drought would find the plants unprepared, and quickly kill them.”

Message received. My roots need pushing, I’m coming to realize.

Scalise concludes his sermon with a quote from the distinguished African American scientist and inventor Booker T. Washington, who wrote: “No one should be pitied because every day of life they face a hard, stubborn problem…It is the one who has no problems to solve, no hardship to face, who is to be pitied…with nothing in life which will strengthen and form character, nothing to call out latent powers and deepen and widen one’s hold on life.”

Faith learned the hard way, I’m finding, is the way out of exile and the path to Eden.

(Greg O’Brien is a career journalist, an author, and a scriptwriter. Alzheimer’s took his maternal grandfather, his mother, and his paternal uncle, and before his father’s death, he too was diagnosed with dementia. O’Brien was diagnosed several years ago with Early-onset Alzheimer’s.)