Posted December 12, 2023

By Greg O’Brien

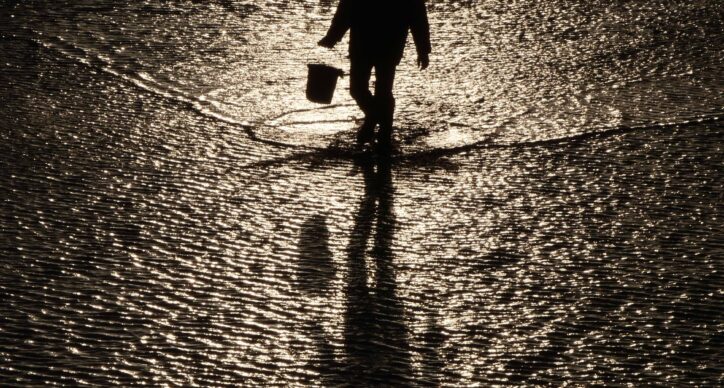

“A light seen suddenly in the storm, snow

“Coming from all sides, like flakes

“Of sleep, and myself

“On the road to the dark barn

“Halfway there, a black dog is near me.”

— Robert Bly, Melancholia, in The Light Around the Body, 1967

The bite of the black dog can be worse than its bark. To some, the black dog is man’s best friend, a faithful companion in the rear of a pickup truck. To others it is a metaphor for the shadows of depression, which comes on strong for many during the holidays, depending on one’s perspective.

I was bitten early in life; the hurt never goes away.

All I know is that often I can’t sleep at night, haunted by demons of depression that keep me captive in the early hours of the morning.

The black dog can be provoked by other diseases, experts advise. Such is the case with Alzheimer’s. The black dog stews in the defective tangles and amyloids of the disease, causing more grave complications.

I know firsthand. Several years ago, I was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s—a disease that can take 20 years or more to run its diabolic course. Alzheimer’s took my maternal grandfather, my mother, and my paternal uncle, and before my father’s death, he too was diagnosed with dementia.

Robert Lewis Stevenson in Treasure Island casts the black dog as a pillaging pirate, a harbinger of violence, with two fingers missing on his left hand. The black dog is haunting me. And so I bury myself in my writing and other work and press on the best I can to rout depression and fight off the treacherous symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

It’s grueling. I feel at times like fighter Roberto Duran in his 1980 assault at the hands of Sugar Ray Leonard when Duran ended his fight by saying “No Mas!”

Depression is not a mood swing, a lack of coping skills, character flaws, or simply a sucky day, a month or a year. It’s a horrific, often deadly, disease. Some choose to deflect the relentless in-your-face assault of these demons, hoping to stare them down for as long as possible. It’s a lonely, numbing gaze, a confrontation that sometimes one cannot win. But losing is not failure; it is evidence of the fight.

Even Winston Churchill fought the ever-present “black dog” in his daily despair. Reflecting on his depression he wrote: “I don’t like standing near the edge of a platform when an express train is passing through. I like to stand back and, if possible, get a pillar between me and the train. I don’t like to stand by the side of a ship and look down into the water. A second’s action would end everything. A few drops of desperation.”

Yet Churchill used his affliction for good; in his case, as a battering ram against Hitler in World War II. Psychiatrist Anthony Storr opined on how Churchill marshaled his depression to enlighten political judgments, observing: “Only a man who knew what it was to discern a gleam of hope in a hopeless situation, whose courage was beyond reason and whose aggressive spirit burned at its fiercest when he was hemmed in and surrounded by enemies, could have given emotional reality to the words of defiance, which rallied and sustained us in the menacing summer of 1940.”

Churchill’s depression, observers have suggested, allowed him to assess fully the Nazi menace and recognize in the process that conciliatory gestures—the policy of England at the time—would only embolden Hitler. Thus, as prime minister, he altered the course of history, attacking Hitler head-on, using his black dog to his advantage. Sic him!

From the start of recorded history, many leaders and creative types, artists and writers, given to mood and anxiety disorders, have used The Black Dog as a lens to the soul. Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Charles Dickens all appeared to have suffered from clinical depression, as did Ernest Hemingway, Leo Tolstoy and Virginia Woolf, to note a few.

“It is often said depression results from a chemical imbalance, but that figure of speech doesn’t capture how complex the disease is,” notes a special health report from Harvard Medical School, titled, Understanding Depression. “Research suggests that depression doesn’t spring from simply having too much or too little of certain brain chemicals. Rather, depression has many possible causes, including faulty mood regulations by the brain, genetic vulnerability, stressful life events, medications, and medical problems. It is believed that several of these factors interact to bring on depression.”

But there are tools to fight—the anacronym “SHIELD,” formulated by world expert Dr. Rudy Tanzi, Chair of the Research Leadership Group for Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, the Joseph P. and Rose F. Kennedy Professor of Neurology at Harvard University, Vice Chair of Neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital, and recently elected to the prestigious National Academy of Medicine. The SHIELD analogy is a means of fighting Alzheimer’s and depression as well. As Tanzi states, SHIELD stands for:

SHIELD is the best antidote for the holidays in fighting depression, far better than belts of scotch. I recall SHIELD’s protections today, as the black dog still roams within me and I look for its leash to reign in the beast and, in a way, make good from evil.