It has long been a controversial theory about Alzheimer’s disease, often dismissed by experts as a sketchy cul-de-sac off the beaten path from mainstream research.

But a new study by a team that includes prominent Alzheimer’s scientists who were previously skeptics of this theory may well change that. The research offers compelling evidence for the idea that viruses might be involved in Alzheimer’s, particularly two types of herpes that infect most people as infants and then lie dormant for years.

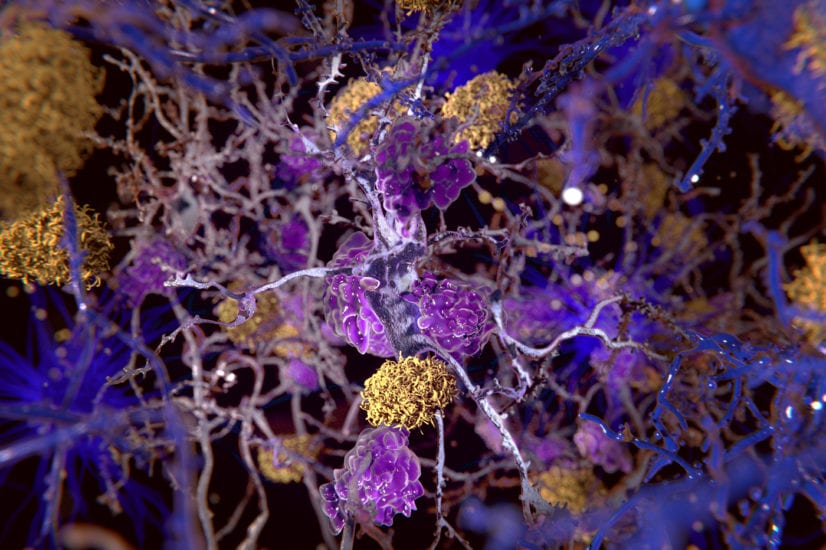

The study, published Thursday in the journal Neuron, found that viruses interact with genes linked to Alzheimer’s and may play a role in how Alzheimer’s develops and progresses. The authors emphasized they did not find that these viruses cause Alzheimer’s. But their research, along with another soon-to-be-published study, suggests that viruses could kick-start an immune response that might increase the accumulation of amyloid, a protein in human brains which clumps into the telltale plaques of Alzheimer’s.

The virus theory is far from being accepted by most Alzheimer’s experts. Some raise the chicken-or-egg question: Could viruses found in greater amounts in Alzheimer’s brains be consequences of the disease or even, as Dr. Lennart Mucke, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease in San Francisco said, “innocent bystanders”? Dr. Mucke called the new study “impressive and very well designed.” But, he noted, “there have been many speculations and even outright claims that infections contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.” “None of them has held up after rigorous cause-effect evaluations,” he added. Still, the new findings will be bolstered by another upcoming study in Neuron, led by Rudolph Tanzi and Robert Moir, neuroscientistss at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard, who have broken ground on the virus idea for years.

Their new experiments, performed in mice and three-dimensional brain cells in a dish, found that the same herpes species ignited a protective reaction in amyloid, a protein present in all human brains. Dr. Tanzi describes this as “seeding” the amyloid, causing it to ensnare the virus in fibrous nets that form plaques. In this way, he said, viruses and other microbes are the “prequel” to the prevailing theory that Alzheimer’s is caused by amyloid accumulation the brain cannot clear out.

For the study published Thursday, Dr. Dudley, who described himself as a “big data guy,” not an Alzheimer’s expert, was asked by the National Institutes of Health to help generate new Alzheimer’s ideas by analyzing information from a consortium involving many brain banks and researchers. Dr. Dudley was interested in whether existing drugs could be repurposed to treat Alzheimer’s, which has so far resisted all drugs tested in hundreds of clinical trials. To start, he and colleagues created computer models mapping the molecular and genetic networks disrupted as Alzheimer’s progresses. But herpes may not be the only infection that triggers the brain’s immune response, Dr. Tanzi said. Bacteria, parasites and other microbes might, too.

“It could lead to new therapeutic strategies down the road,” said Dr. Eric Reiman, executive director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix and one of several Alzheimer’s experts and longtime virus-theory skeptics who were co-authors on the study.

For example, experts said, it might make sense to develop vaccines or drugs to pre-empt infections most linked to Alzheimer’s and to screen people for genes that increase vulnerability to those infections. The goal, said Dr. Reiman, is to “find better ways to understand and treat the disease — including ways that may defy preconceived notions.” Dr. Dudley said he is unsure whether many mainstream Alzheimer’s researchers will endorse the virus idea anytime soon. “It’s very unpopular,” he said. “I’m sure there’s a lot of people who are secretly unhappy about it.” Still, he said, Alzheimer’s researchers “come up to me at conferences and say in hushed tones, ‘Oh, I also have a data set that shows viruses, but I’m afraid to publish it.’”