It’s a Sunday morning and my wife and I are arguing about the previous night’s dinner party.

“No one would let me talk,” Laurie says.

“What do you mean? Of course they let you talk.”

“No. They’re all just talking constantly and I never get a chance to say anything.”

“But Laurie, that’s what happens at dinner parties. You’ve got eight people fueled by a lot of alcohol and they all are clamoring for the floor. That’s just the way it is.”

“I didn’t get to speak. I hated it. Why won’t they let me speak?”

I’m puzzled. Laurie was always the life of any get-together: raucous, loud, leading the room from one topic to the next. What was going on?

At another dinner party a few weeks later, I notice Laurie sitting back, silent. “Hey Laurie,” I say in a loud voice. “Anything you’d like to add?” The room quiets and everyone looks at her.

“No,” she says, and sips from her glass of wine.

The next morning we’re arguing again. “No one,” she says, “would let me speak.”

I’m sitting in the living room in 2011, reading.

“He’s coming over with the stuff to do the thing,” Laurie says.

It takes me a moment to realize she’s speaking to me. “What?”

“He’s coming over with the stuff to do the thing.”

“What stuff? What thing? And who is he?”

She glares at me. “You know.” The words are accusatory and full of weight.

I wonder if I am becoming that stereotypical husband who ignores his spouse, just responding “Uh-huh, uh-huh.”

“I’m sorry. I must not have been paying attention. Who’s coming over?”

She turns and walks out of the room.

We’ve flown to Washington to visit our oldest daughter, Lauren, at college. We get together for drinks with one of my brothers. “She’s doing the thing pretty soon,” Laurie says.

“What?” my brother asks. “Laurie, seriously, we need to find out what’s going on with your speech. Something’s up.”

Laurie looks shocked, and says, “What do you mean?”

“Your speech, the way you talk. I don’t understand what you’re saying.”

She laughs. “Oh, that’s nothing. It’s the beer.”

When Laurie gets up to go to the restroom, I say to my brother, “You’ve been noticing it?”

“Everyone’s been noticing it,” he says.

“I thought it was just me.

Worried, I reach out to Laurie’s primary care physician, asking her to refer Laurie for tests. She talks to Laurie, who eventually agrees.

When we meet with a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital to find out the results, he says Laurie has “primary progressive aphasia of the logopenic variant.”

“What’s that mean?” I ask.

“It’s aphasia” — an inability to communicate — “and it’s specifically word-related. That’s the ‘logo’ part. Laurie’s having trouble finding words. That’s our primary diagnosis.”

Then he says, “And it’s progressive.”

“Progressive?” I ask.

“Meaning it’s going to get worse.”

I’m bewildered and want to know what caused it. Did she have a stroke? Heavy metals, pesticides? He says probably not, but can run more tests to check.

“Well, I think we need to,” I say. “Right, Laurie?” She nods.

“This is just crazy,” I say. “She’s only 56.”

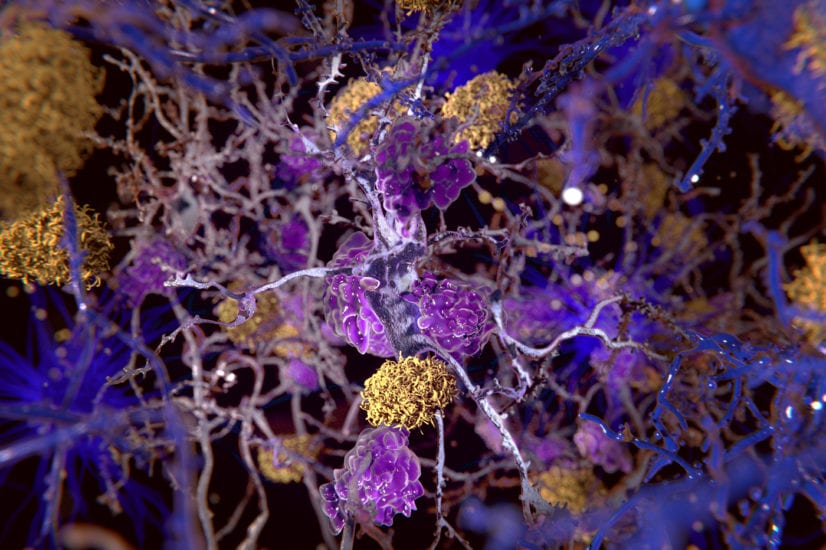

We stand up and the neurologist asks me to stay behind for some paperwork. As Laurie waits outside, he says, “I didn’t want to say it in front of her, but in all likelihood what she has is younger-onset Alzheimer’s. It just started in a unique part of her brain — the left rear lobe — but like all Alzheimer’s, it eventually will spread throughout the entire brain.”

“You need to prepare yourself,” he adds.

Alzheimer’s? I thought that only happened to people in their 80s and 90s. “But she’s only 56,” I repeat. “She’s got her MBA in finance.”

Laurie and I had first met at a punk-rock club in Washington, where I’d moved for work in 1982 after graduating from law school. I was there with friends when she walked in, 5 foot 11, tan, wearing a black miniskirt. I spent the evening glancing her way, occasionally approaching but then backing off, certain she was out of my league. Toward midnight, I finally went up to her and managed to say “Hello.”

Giving me a withering look, she said, “Well, it took you long enough.” I was smitten.

She would turn out to be the wittiest, smartest, and most talkative person I had ever met. And now all of that was fading away.

We’re at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, walking into a small conference room to meet with a neurological researcher. Months earlier, Laurie had agreed to be part of his study testing whether a combination of certain dyes in the bloodstream and positron electron tomography imaging could pick up the presence of abnormal amyloid proteins in her brain. This is a marker of Alzheimer’s disease, usually only found in an autopsy.

The researcher is hoping his technique can detect Alzheimer’s before death. We’re hoping he’ll tell us her increasingly apparent aphasia is caused by something else.

We sit down. He picks up a piece of paper, looks at it, and then looks at us. He starts to cry.

Laurie is standing in the middle of our living room, sobbing. I go to her and hold her. I don’t need to ask what’s wrong; I know. We just stand there, hugging.

A few days later, I look in the medicine cabinet at Laurie’s medications, Aricept and Namenda, representing the only two types of Alzheimer’s-related drugs on the market. Neither stops the disease, let alone cures it, but they’re thought to help improve cognition. The containers seem full. Too full.

“Laurie,” I ask, “Have you been taking your pills?”

“No,” she says. “I don’t need them.”

“Yes, you do,” I say. “You need them for your Alzheimer’s.”

“I don’t have Alzheimer’s,” she says.

Laurie comes out the front door along with our youngest daughter, Bryn, to see the new Honda CR-V I’m driving.

“I want to try it,” Laurie says. Bryn and I exchange looks. It’s 2015 and I haven’t let Laurie drive for months, finding one excuse or another. But I reluctantly say OK, and we climb into the car, me in the front passenger seat, Bryn in back. I suggest we go to get lunch at one of our regular places, an easy drive on mostly back roads.

At the first stop sign, I remind her to take a right. She immediately starts to go left. “No!” I say sharply, “The other right!”

She takes the next turn without appearing to think. She seems to be doing fine, and I begin to relax. A quarter mile later, at a light, she asks “Where?”

I point to the left, and she turns that way. At the restaurant, she cruises toward a parking spot right in front. I realize she’s about to hit a car to our left. I reach across and pull the steering wheel down so we swerve right, saying “Laurie, stop. Stop!” She does.

“Let me park it,” I say. She gets out, and I get in.

After lunch, I drive home. Bryn and I have a few minutes alone.

“That was awful,” she says. “She shouldn’t be driving.”

Later, Laurie tells me that “it’s the new car. I was fine with the old one.”

Laurie walks into the apartment, her face ashen. “Is everything OK? Did you get the money?” I ask. She bursts into tears. “It’s not working.”

I stand up, go to her, and hug her. “It’s no big deal. Let’s go down and take a look. Maybe the ATM’s just broken.”

We go across the street. I watch as she puts her card in and types her password. The screen reads “incorrect password.” She tries again and the error message flashes once more. “What’s your password?” I ask.

“Umm.”

“I’m pretty sure it’s our anniversary,” I say. “Try typing that in.” The numbers she presses are nothing close to our anniversary.

“Laurie,” I say, my voice rising. “Pay attention. That’s not your password.” I catch myself and try to cool down. I ask her to let me help, and type in the password. A few seconds later she has $60 in her purse.

I’m sitting in our bedroom and I hear the click of a door shutting. I get up and look around. “Laurie?” There’s no answer. I walk outside to the hallway. No sign of her. I take the elevator to the lobby and see the doorman. “Have you seen Laurie?”

“Not this morning,” he says. I run up the stairs and find her between the second and third floors. “What are you doing here?”

She looks at me, bewildered.

She got her MBA in finance in 1986, shortly after we got married. An ardent feminist, she kept her own name and we gave our children both of our surnames. She wrote, acted in local plays, ran film groups, and threw herself headlong into our children’s lives.

I sit and contemplate how much Laurie has lost. She can no longer write. She can’t even sign her own name. The television’s remote control mystifies her. When we go out for dinner, she can’t read the menu. She no longer showers, seemingly afraid of the water. She wears the same clothes, day after day. Her hair has grown ragged and when the telephone rings, she simply looks at it.

I understood the word “progressive” when her neurologist first diagnosed it. But I realize I never really absorbed it, fooling myself into thinking that however she was would remain the same way. When I’d notice some new diminishment, I’d just reorder my thinking, believing that this was now the new normal.

I now understand none of that’s true. I’ve lost her. And she’ll never come back.

I’m nervous. For months, Lauren, Bryn, and I have been talking about a next step for Laurie. I travel a lot for work; I can’t care for her at home anymore. We’re worried about her wandering. After touring places, we settle on Avita of Needham, a memory care facility. Today, June 29, 2016, is the day she is supposed to move.

But Laurie seems completely unaware.

A care manager we hired to help us is at the apartment. “Laurie,” she says, “Tom needs to go on a long business trip. He’s going to be gone for a while.”

Laurie looks terrified. “Do you feel afraid to be alone?” she asks. Laurie nods.

The care manager continues. “I know a place that’s safe and fun and where you get to play brain games. Doesn’t that sound good?” Laurie nods again. “Would you like to visit with me?” Laurie nods a third time.

We go to the car and after a short drive are walking through the front door of Avita. The executive director greets us. Everything has been carefully staged. She and others gather around Laurie, hugging her and talking and leading her down a corridor and past a locked door. She doesn’t turn around to look at me.

That night in bed I realize she’ll never sleep next to me again. Despair washes over me.

I call frequently to find out how she’s doing, but I don’t visit. The idea is to give her time to adjust, to become acclimated.

After two weeks, I finally come in to see her. I’m waiting for the questions — “Where have you been?” “Why am I here?” “Can I go home now?” — and rehearsing my answer — “This is your home now.” I’m preparing for the tears and anger.

There’s none of that. We visit, have a cup of coffee. I talk; she listens. I walk her back to her room, she sits in a chair, and I leave.

This really is her home now.

Nine months later, Laurie and I are sitting in the living room at Avita. “My mother died yesterday,” I tell her. They had been close. Laurie turned to my mom when the children were first born and she felt out of her depth, wondering how she would ever manage motherhood.

Laurie just looks at me and stares.

It’s been a year and a half, and Avita’s executive director tells me Laurie needs more care than the facility can provide. I am not surprised.

When Laurie first entered, she could manage most everything, only needing some persuasion to take her medication or brush her teeth. Now she’s largely incontinent, increasingly needs help eating, and is unsteady on her feet.

Laurie gets in the car with Bryn and me for another ride to another new home, the Hebrew SeniorLife facility in Roslindale. Where Avita felt homey and calm, HSL — as excellent as it turns out to be — has a more frenetic, institutional feel. We take an elevator to the fourth floor and find her room. She’s placid and uncomplaining, seemingly oblivious to her change of circumstances.

A few weeks later, I sit down with HSL’s medical team to review her case.

“Except for Alzheimer’s, she’s probably healthier than most of us,” the nurse manager says.

It’s true. She takes no medication except for those connected to Alzheimer’s. Yet even though the rest of the folks on her floor are older than her by a generation or more, cognitively she’s one of the worst off. For the most part, they can still speak, tell stories, play bingo and trivia, talk about the football game on TV. Laurie, once so vital, can’t do any of those things.

Lauren, Bryn, and I sit in Hebrew SeniorLife’s family dining room in 2018. We’ve picked up subs for lunch and gather around a table, feeding Laurie her lunch. She looks at us, her face brightening. “Who am I?” asks Lauren. Laurie gives no response. “Am I Salem?” That’s one of our cats. “Am I Bryn?”

“B-b-b,” Laurie says.

We’re familiar faces. But does she know why? Does she know I’m her husband? That Lauren and Bryn are her children? I don’t think so.

Three or four times a week, I have lunch with Laurie. I sit next to her and cut up her food, navigating forks and spoons to her mouth, trying not to spill her soup. After the kind of “open your mouth” urging I once gave the kids, she’ll take a bite and chew.

Meat loaf is today’s offering. Laurie takes a bite or two but I notice she’s not really chewing. Instead, she tucks the food away in her cheek. I offer some cranberry juice, usually a favorite, but she swallows only a little.

I look at her closely. Her hair is almost entirely black. Her face is remarkably unlined. I stroke her hair and she pays me no mind, never glancing my way. She’s here, I think, but not really here at all.

I’m out of town for a family wedding, having brunch with Lauren.

“Something’s changed with your mom,” I say. I describe how her eating has become more tentative. “Plus, she’s losing weight.”

“Should I come up to Boston?” Lauren lives and works in New York City.

“Probably not,” I say, not wanting her to take an unneeded vacation day. “Let’s see what the doctor says.”

The next day I’m back in Boston. Bryn and I walk into the dining room at Hebrew SeniorLife, ready to have lunch with Laurie. We scan the room and can’t find her. I see her aide. “Where is she?” I ask.

“We couldn’t get her out of bed today,” the aide says.

Bryn and I go to see her. Laurie glances at Bryn and smiles with what might be some recognition. Otherwise, she seems only semiconscious. When the doctor comes, he tells me she’s not taking in any liquids.

“What does that mean?” I ask.

“Seven to ten days,” he says.

I feel like I’ve been hit in the gut.

He says they could give her fluids intravenously, or put a tube down her throat to feed her. Years earlier, the girls and I had talked about such a moment. Back then we had decided we wouldn’t take any extraordinary measures. That decision, once abstract, now seems almost unconscionable. How can I let her die?

There are tears in my eyes now and I say, “No, I don’t think we should do anything. Just keep her comfortable.”

I call Lauren and tell her she should plan to come up in a few days. The next day Laurie seems fine, resting easily, but the following morning her breathing is labored.

It’s been seven years since Laurie was diagnosed, almost three years since she went to Avita and 14 months since she was admitted to Hebrew SeniorLife. Day after day, the disease progressed almost imperceptibly. But now it’s moving too fast.

The charge nurse warns me Lauren should come. Now.

“Alzheimer’s proceeds slowly, almost invisibly, on its destructive course. It’s like the transition from summer to fall,” I say, looking out at familiar faces at Boston’s Old South Church. “The green leaves turn red or yellow or orange, but we never actually see them change. It’s just that, one day they’re green and suddenly, they’re not.”

“But while leaves turn color over a brief period of time, Alzheimer’s takes years. And that amount of time, those long, long years, sometimes makes it hard to remember the days when the leaves were green, hard to remember the woman we all knew.”

My voice breaks. It’s true. The last seven years have been so overwhelming that I find myself hard-pressed to remember what came before. What was life like before neurologists and researchers and memory care facilities, before halting speech and blank stares?

I sift through photos. The two of us walking in a field. Laurie beaming at our wedding. Her driving a car, sunglasses on, turning with a slight smile for the camera. Catching up with her best friend from childhood. A family Christmas card. She and Bryn mugging for the camera. Lauren’s high school graduation. These are the memories that I want to hold on to, the days when her mind sparkled, her smile was bright, and the future beckoned.

_____________

Tom Keane is a writer in Boston. Send comments to magazine@globe.com.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/01/07/magazine/my-wife-couldnt-have-alzheimers-she-was-only-56/