Posted April 18, 2023

By Greg O’Brien

Do the math. You don’t have to be a genius. Yet the statistics are so staggering one can’t count on their fingers.

“More than six million people in the United States now have Alzheimer’s disease—and it is estimated that four million (two-thirds) are women,” notes the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (https://curealz.org/).

And that doesn’t include caregivers. An estimated 66 percent of all caregivers are women—many of whom have to leave their jobs or reduce work hours to provide care.

Something to think about as Mother’s Day approaches and we have celebrated Women’s History Month.

Yet the history of women and Alzheimer’s is not something to revel in. It’s personal to me.

I lost my mother, the hero of my life, Virginia Brown O’Brien, to Alzheimer’s, which also took my maternal grandfather, my paternal uncle, and before my father’s death, he too was diagnosed with dementia.

Years ago the disease came for me.

The cause of why women disproportionately suffer more from Alzheimer’s than men is not fully known yet; the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund and others are investing in research to understand sex-based differences in the development of the disease, which also unduly affects Hispanics and African Americans.

While no two forms of Alzheimer’s and other dementias are perfectly alike, my mother, in so many ways, personifies the courage of women with this disease.

****

Mother’s Day has a way of bringing us back to the womb, providing perspective beyond a Hallmark card or bouquet of flowers—flashes of reflection, a carousel of streaming images on an old-school slide projector embedded in the mind.

My mother was a stunning woman, barely five feet, three inches, 105 pounds, with a genius IQ; she gave birth to 10 children, an accomplishment in itself. Over the years, she taught me to think, to forgive, to love, and how to speak and write from the heart, the place of the soul, when the mind fails. I’ve never forgotten that.

My mother was no more perfect than anyone else’s mother, yet in her Alzheimer’s, she was a composite of her generation—the dutiful spouse of the Greatest Generation, a generation, though, that whiffed on the selfless, extraordinary accomplishments of women.

Yet, while my mother brimmed in gifts of the spirit and love, she never was a great cook. Sorry, Mom…We can’t be perfect in all ways…

A second-generation Irish American with close ties to County Wexford, she boiled everything gray. To kill the taste at our house in Rye, New York, outside Manhattan, we all used salt and liberal amounts of Ketchup, Irish gravy, to kill the taste. In the cluttered kitchen of our family home on Brookdale Place in Rye, New York—not far from the Upper East Side of Manhattan where my mother grew up—the pot roast simmered in a crock pot on Sundays from morning Mass until early evening. The hoary smell that wafted through the three-story stucco home remains with me today—a scent that seemed at times to peel the wallpaper off.

But out of the kitchen, my mother was stunning.

She loved yellow – the symbolic color of the mind and the intellect, the third chakra in the solar plexus, representing personal power and spark. Yellow is the hue of memory, hope, happiness, and enlightenment. Yellow inspires the dreamer, encourages the seeker. My mom’s rapture with yellow was an upward, heavenly turn in her stages of grief.

Yellow also is a color of angels, and in scripture it symbolizes a change for the better. My mom, who died years ago in a bruising battle with Alzheimer’s, believed in angels. I do as well. The word is derived from the ancient Latin “Angelus,” translated “messenger” or “envoys”— one that resonates with peace.

As a teenager, I often noticed my mother standing at the kitchen window overlooking a corn patch with Rye Brook in the distance, meandering to Long Island Sound. She was talking to herself, fully engaged in conversation. I wasn’t sure with whom. At first, I thought it was a way of deflecting the stress of raising a brood of kids with a collective attention span of a young, yellow Lab. The disengaging increased: misplacing objects, loss of memory, poor judgment, seeing things that weren’t there, and yes, the rage—all warning signs years later that I began noticing in myself.

After my father, Francis Xavier O’Brien, retired as Director of Pensions for Pan Am and my mom left her teaching job, my parents moved to Cape Cod, a few miles from me, settling into our Eastham summer home, not far from Coast Guard Beach. I felt privileged to be the only sibling living on Cape, though with favor comes responsibility. Ultimately, I took on the responsibility as family caregiver.

Over time, my father developed prostate cancer, severe circulation disorders requiring several life-threatening operations, and dementia—rendering him to a wheelchair. My mother progressively continued her cognitive decline into Alzheimer’s, but fought off the symptoms like a champion to care for my father, once a swashbuckling World War II Navy captain.

It was a perfect yet flawed marriage in some ways out of need: My Dad became Mom’s memory, and my mother became his arms and legs. They had morphed into one.

“I can’t get sick; I can’t get sick,” my mother kept saying when all the siblings urged her to see a doctor. “I can’t get sick. I have to take care of your father!”

Yet, she was sick, and she knew it.

The forewarning signs were textbook and frightening. Over time, she began sticking knives into sockets; hiding money, wads of it; brushing her teeth with liquid soap; refusing to shower; not recognizing people she had known all her life; serving my father coffee grinds for dinner.

Then one Sunday afternoon at the cottage the disease began to overtake more. I brought my mother a photo of all her children from a recent family reception that she had missed. She couldn’t name one of us, including me. She had no clue and was still driving at the time and leaving bags of garbage in the trunk of her car. As I left my parent’s home that night, I could only think of the jarring interjection in the movie JAWS, when Chief Brody first encountered the mammoth shark: “YOU’RE GONNA NEED A BIGGER BOAT!”

We had a leaking dinghy at the time. Two weeks later, ironically Independence Day weekend—with my dad continuing his decline from dementia, acute circulation disorders and internal bleeding resulting in numerous fire drill ambulance runs to the hospital with Mom in tow—my mother took me aside and said she was about done.

“I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” she told me. “I’m not sure how long I can hold on…”

Instinctively, I reassured her that the family had her back, all of us, but I felt this penetrating sinking feeling that we were at the precipice of a steep cliff, and ground was giving way. Hours later, I got an emergency call that Dad once again had been rushed to Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis. Mom was with him, yet another fire drill. The nurse told me to hurry.

I met my parents in the emergency room, filled to the brim with the walking wounded of summer. It took 36 hours to get my father into a hospital room. About 28 hours into the ordeal, I noticed that my father, sitting in his wheelchair in an emergency room cubicle, was bleeding onto the floor—a pool of blood. In a panic, I tried to divert my mother’s attention. It was too late. She was horrified. I could see it in her face; she was done.

“I’ll get the doctor, Mom, don’t worry,” I said as I raced for the door.

She grabbed my right elbow from behind. “Greg, would you take over,” she asked quietly.

“Yeah, Mom, I’m getting the doctor now,” I said. “I’m getting the doctor…”

“No,” she replied as I continued for the door. “Would you PLEASE take over?”

I stopped in my tracks.

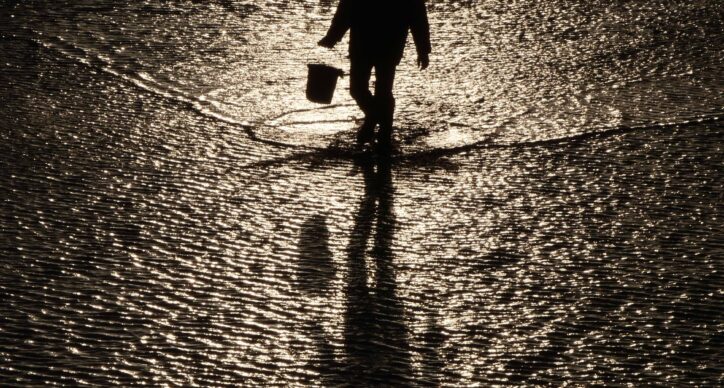

Something inside me said that she was saying goodbye. I turned and looked into her eyes. It was as if someone had pulled down a curtain. As I watched her, I had the feeling of seeing a person, who had been holding on to a dock on an outgoing tide, let go. I saw her drift. Within ten minutes, she curled up like a kitten in my dad’s hospital bed, while he sat unconscious, bleeding in his chair.

Who are the parents now, I thought?

My father died first, and four months later my mother passed away in a nursing home near my house. Upon my father’s death, she told me: “I’m not sure how much longer I want to hang around here.” The hardest thing for me and my siblings was to take my mother to a nursing home. She went there to die. I knew that and visited her almost daily.

I got a call one night from the nursing home. ‘Your mother is not doing well,” the nurse said. “She’s scared. She needs you. Please come here!”

I raced to the nursing home in my yellow Jeep along a dirt road through the woods, hitting all the potholes left behind from the trotting of horses on this country way—rear wheels sliding left, then right as I pressed ahead. When I arrived minutes later, my mother was deep asleep. I woke her to let her know she was not alone.

“Mom, I’m here. Sorry to wake you up, but I wanted you to know I’m here.”

“No Greg,” she replied. “I’m happy you’re here.”

Rebuffing Alzheimer’s stereotypes, it was the first time in almost a year that my mother could remember my name. There was a peace to her that said something was about to happen.

I had put a framed black and white photo, sepia tone, of her father on a wall at the foot of her bed, so every morning when she awoke, she could see her Dad looking down at her. I felt his presence.

Sitting down next to her bed, I put my right hand over my mother’s left hand. Slowly, she put her right hand on top of my hand. We talked, as one can on the steps of death. I waited until she fell back to sleep, then kissed her on the forehead as I prepared to leave.

Again, pushing back on dementia stereotypes, her beautiful green eyes opened wide. “Greg, where are you going?” she said in a soft voice.

Knowing in my soul that the moment was at hand, I sat back down, held her hand again, looked into her eyes, and said, “Mom, I’m not going anywhere. We’re gonna ride this one out together …”

I had trouble in the moment finding the peace of death. But I stayed by her side until she fell back to sleep again. Then I kissed her on the forehead, knowing the long kiss goodbye was over.

She never woke up.

Still, my mother had my back again a few months later in an encounter on stage in Beverly Hills where the Golden Globe Awards are presented. I had been asked to speak before 1,000 Hollywood celebrities at an Alzheimer’s fundraiser and Hollywood revue called “A Night at Sardi’s.” The stars were out that night in clusters.

The evening was hosted by David Hyde Pierce from the award-winning TV show, “Frazier,” and featured performances by the cast of “The Big Bang Theory,” Joey McIntyre, Jason Alexander, and Grace Potter. Seth Rogen and other A-listers presented as well.

Backstage before my speech, I was incredibly nervous. Few get to stand in this place. I told myself to calm down, that I’m doing this for my Mom, for all she had taught me.

I then heard a soft, confident voice inside that said, “Greg, you rock this! You just rock it!”

And so I did.

At the podium, I noticed there was an older woman standing behind me. She made me feel so relaxed in the moment, encouraged, and loved. Several times I wanted to turn around to see who it was, but felt I needed to stay focused, just focused.

After my speech, I turned around, and the woman was gone.

Back at the table, I asked my wife Mary Catherine: “Who was the woman standing next to me? She made me feel so at peace, so encouraged. Who was she?”

“What?” my wife said. “What…Greg, there was no woman behind you on the stage. No one!”

I asked eight others at our table.

“Greg,” they all said. “You were alone.”

“No,” I interrupted, “I was not alone. The spirit of my mother was standing behind me, and perhaps the souls of others consumed by this demon called Alzheimer’s.

Do you believe in angels?

Greg O’Brien, author of On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s, is a career journalist and an advocate nationally for finding a cure for Alzheimer’s. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GregOBrien.Author.OnPluto/