Posted March 23, 2015

As reported recently in the New York Times (Business Day, March 20, 2015, “Biogen Reports Its Alzheimer’s Drug Sharply Slows Cognitive Decline”) and other media, the pharmaceutical company Biogen has announced impressive results in a Phase I “human safety” trial of a new drug designed to treat — and possibly prevent — Alzheimer’s disease. The drug, aducanumab, lowered brain Abeta levels and slowed decline in cognitive function compared to a control group of Alzheimer’s patients receiving a placebo.

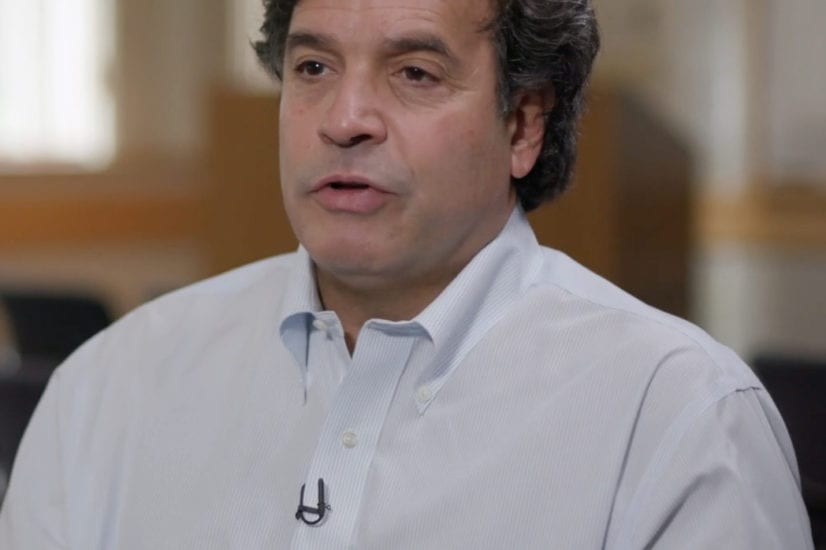

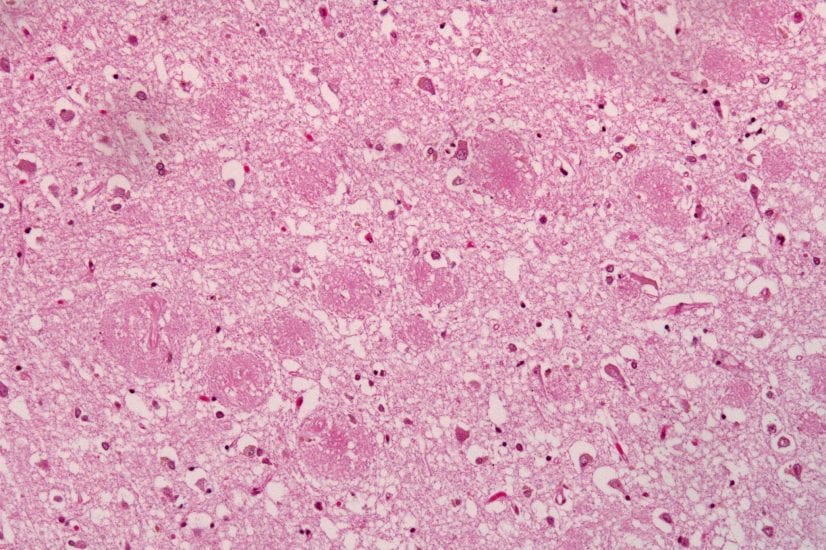

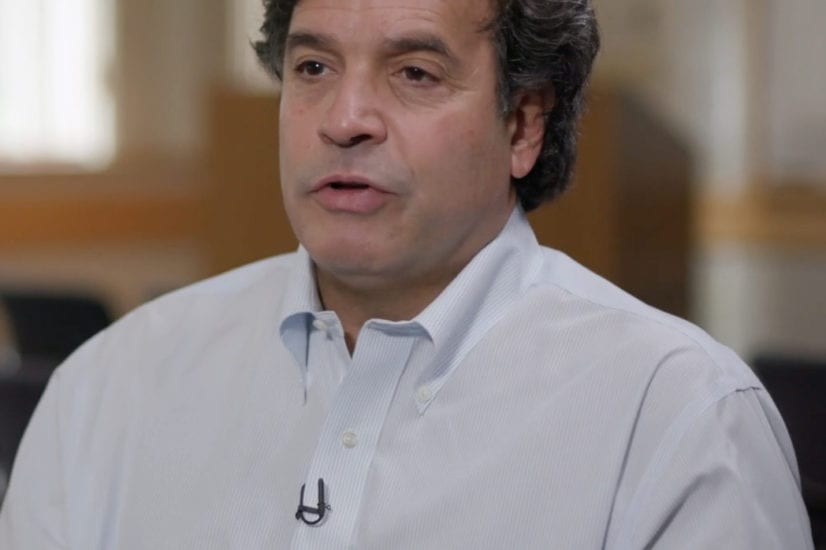

“Hats off to Biogen — this is an extremely important breakthrough,” commented Rudy Tanzi, Ph.D., chair of the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (CAF) Research Consortium. “It is the first trial showing that lowering Abeta levels in the brain can slow down cognitive decline in patients. It also nicely dovetails with several active CAF projects. Most importantly, it further validates our understanding of the disease, from genetic studies, showing that amyloid plaques initiate the disease by causing the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and inflammation. The Biogen study offers the first proof that if you can stop the accumulation of Abeta in the brain, you can slow down or even stop the disease in its tracks.”

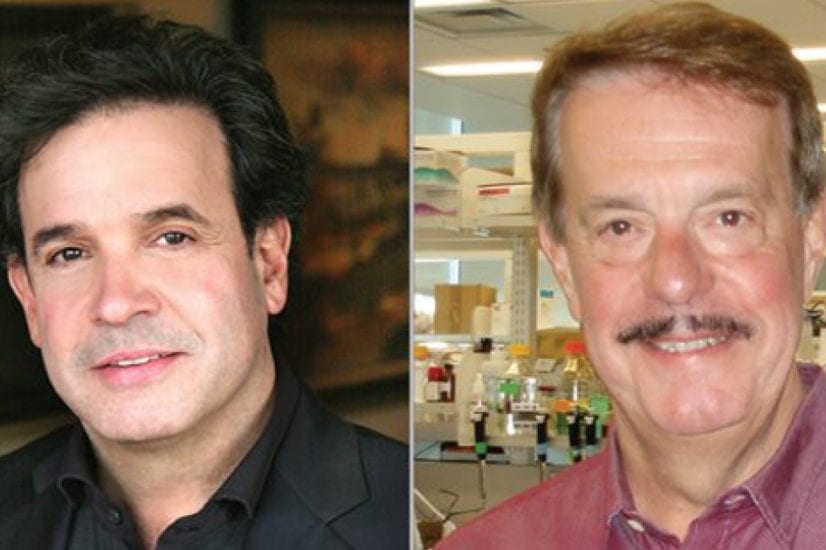

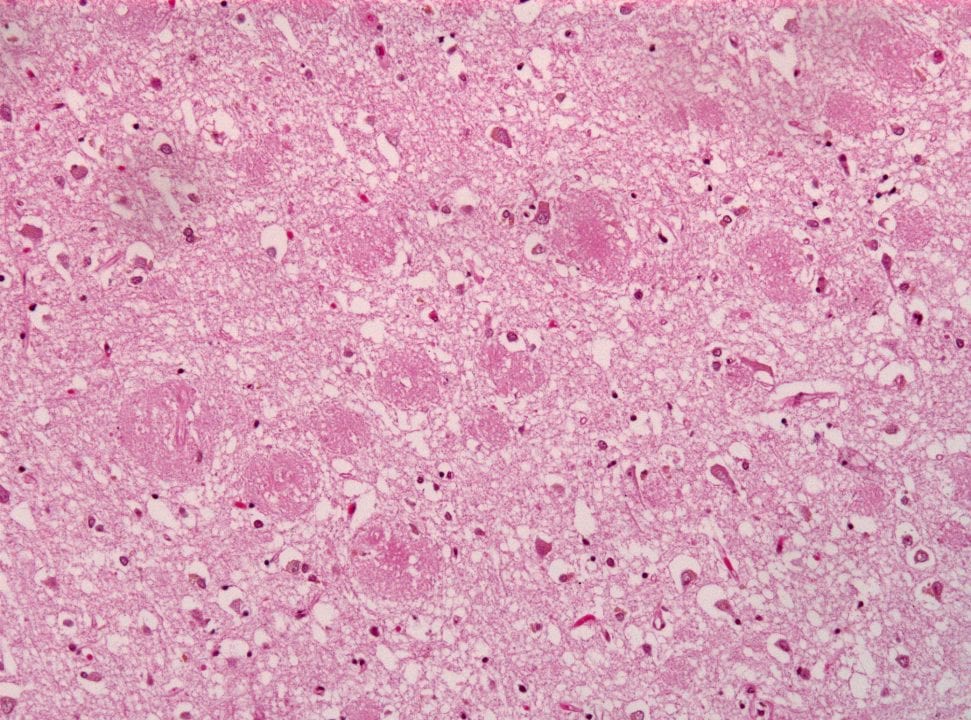

Biogen’s new drug is a reproduction of a naturally-occurring human antibody that removes Abeta “plaques” from the brain, potentially stopping the disease from developing any further. If administered early enough, this approach could potentially prevent the development of any Alzheimer’s symptoms. We have known for years that the body produces naturally occurring antibodies to Abeta, called “beta-amyloid auto-antibodies”. In 2005, Dr. Tanzi and Dr. Robert Moir at the Massachusetts General Hospital Genetics and Aging Research Unit reported that auto-antibodies naturally made by the body to defend against clumped up aggregates of Abeta are depleted in Alzheimer’s disease. Meanwhile, they appear in higher concentrations in younger unaffected subjects. Based on these findings, Tanzi and Moir proposed in 2005 that since the naturally occurring antibodies were protective against age-related onset of Alzheimer’s when present in high concentrations, they could be a powerful therapeutic for treating and preventing Alzheimer’s disease.

The root studies of the new Biogen therapy, aducanumab, were carried out by their partner, Neurimmune, a Swiss Biotech company. The drug screen was based on seeking out the most potent naturally occurring auto-antibodies against Abeta deposits and then mimicking them to treat the disease. In a very clever approach, the Neurimmune scientists isolated the anti-beta amyloid antibodies from centenarians with remarkably intact cognitive abilities. The assumption was the centenarians were highly protected against Alzheimer’s because they possessed potent protective antibodies against Abeta, similar to those described by Moir and Tanzi in 2005. The bet paid off when Neurimmune’s partner, Biogen, announced in the completion of the Phase I clinical trial of 166 patients that their new antibody treatment reduced amyloid levels in the brain and correspondingly slowed down cognitive decline over the course of about one year.

While the new Biogen therapy shows great promise as it heads directly into a much larger Phase III “efficacy” trial, there are also some concerns, Tanzi noted. “While we are very excited and optimistic about the new Biogen therapy, there is still a lot of work yet to be completed and we cannot just assume that the next trial (Phase III) will be a slam dunk.”

First, the significant cognitive results using the specific memory tests that the FDA bases approval upon, came only from the highest dose group. There were 32 patients in this group versus 40 patients on placebo. “These are still small numbers,” Tanzi said. “so, while we are very hopeful, is not guaranteed that the results will be replicated in the larger Phase III trial.”

Second, the placebo group had a larger decline in cognition over one year than has normally been observed in trials in the past. This may have contributed to a relatively large difference in cognitive decline between the placebo group and the high-dose group. If, in larger trials, the placebo group declines more slowly, it is not guaranteed the treatment groups will attain statistical significance for slowing down cognitive decline.

Third, there were some side effects, most notably brain swelling and headaches. “These side effects generally resolve on their own over time,” said Tanzi, “but they are a potential concern since they could lead to drop out of patients from future trials”. The side effects were most prevalent in the highest dose group and in carriers of the APOE4 risk gene (present in 60-70% of Alzheimer’s patients).

CAF has long supported the development of other anti-amyloid treatments, and is several years into a program developing a class of drugs called “gamma-secretase modulators” (GSM) that would also clear amyloid from the brain. While Biogen’s drug would have to be injected and will likely be very expensive, the GSM drug would be taken in a less costly and more convenient pill form. The GSM project, led by Tanzi and Steve Wagner, Ph.D, at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), has been co-funded by CAF and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators hope to get the drug into Phase I trials later this year.

“This announcement also bodes well for our planned screen of ‘Alzheimer’s in a Dish’ aimed at finding more anti-amyloid (and anti-tangle) drugs,” said Tanzi. “We have our work cut out for us. But the prospects for our multi-track approach look better than ever thanks to impressive success of the new Biogen trial of aducanumab.”